Above: A bear snacks on birdseed after smashing a bird feeder at a home in Andes in 2006. Photo by Peter Possenti (using a telephoto lens.) Used with permission.

The spot Tim Meservey found at the base of a tree early one Saturday morning in September was a hunter’s dream. On a rise, it faced a gully that is a country lane for wildlife. A few hundred yards away is a farm where bears strip sweet, young corn from the stalk when no one is looking.

Usually, bears are not on Meservey’s big game list. Not as plentiful as deer, they are also elusive, and it was rare to see one in the woods by the time regular hunting season arrived in November in Greene County, where the 39-year-old hunter and middle school art teacher lives.

“They tend to head back up in the mountains in fall,” Meservey said.

But when the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) initiated an early bear season that started on Sept. 6 – the regular season opened Nov. 15 – Meservey said he finally saw an opportunity.

By 6:45 a.m. on Sept. 13 he was on the ground by the tree in the town of Catskill, looking out beneath the boughs of the oaks and maples ahead.

Nearly an hour later, he was still there. A stubborn ground fog he hoped would clear still hung low over the gully.

“I was questioning, ‘Why am I out here wasting my time sitting in the woods looking for a bear,’ when suddenly the fog lifted,” Meservey said. The first big black bear he had ever seen in his life walked into view.

From 75 yards away, Meservey aimed his rifle. Worried that the shot would not be good, he yelled. The bear stopped, looked over, and Meservey fired. The bear collapsed.

“It was luck,” Meservey said, “and being in the right place at the right time.”

Above: The 580-pound bear Greene County hunter Tim Meservey shot during the early season in September 2014. Photo courtesy of Tim Meservey.

Luck or not, Meservey’s bear is part of a tally that the DEC will use to determine the impact of the early bear hunting season on the agency’s goal to reduce the bear population in several parts of the state.

Clashes between bears and humans in the Catskills are on the rise, DEC officials say. The agency is betting that a smaller bear population will mean fewer bears breaking into houses, upending trash cans and threatening people and pets.

Final figures for the 16-day season, which ended Sept. 21, and the subsequent bow, regular, and muzzleloader seasons are not yet ready. But the DEC did give the Watershed Post preliminary data that indicates hunters like Meservey may have helped make the 2014 bear hunting season one of the strongest on record for the Southeastern region, which includes the Catskills.

Above: The number of bears killed in New York State by year. Data from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

“It did seem to be a very good year,” said Matthew Merchant, a wildlife biologist with the DEC. “Don’t know for sure, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s another record.”

Data collected so far from hunters and cooperating taxidermists show that hunters killed about 1,195 bears in New York in 2014, about 600 of them in the Southeastern region of the Southern Zone.

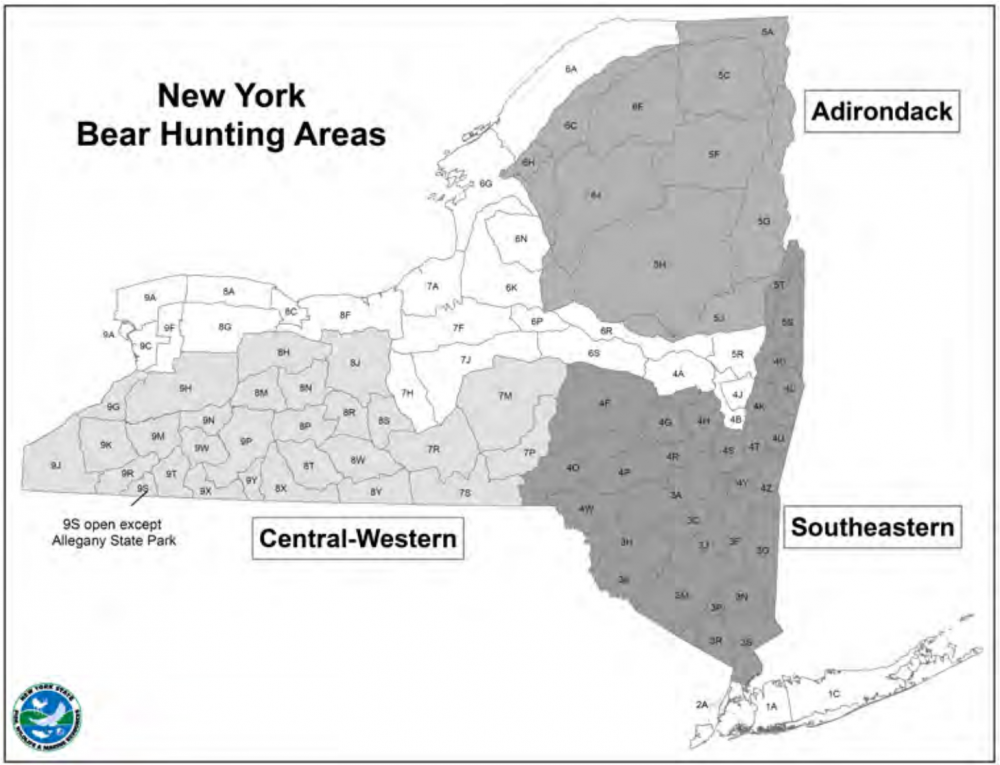

Above: The DEC’s bear hunting regions. Source: New York State Black Bear Harvest Summary for 2013.

Of that 600, about 250 bears were taken during the early season, which was established in portions of the Catskills and western Hudson Valley.

In the 2013 hunting season -- when there was no early season -- hunters killed 1,358 bears in the state, of which a record 636 bears were taken in the Southeastern range.

Officials are still collecting and analyzing the data for the 2014 season, which ended ended Dec. 16 in the Southeastern region except in Westchester, where it ended on Dec. 31.

Final numbers are expected to be released late February or March.

Merchant, who is based in New Paltz, said he thinks the strong 2014 numbers can be attributed to the early season and to a good crop of acorns and beechnuts.

“Allowing people to use firearms gives hunters the combination of getting bears while they are still out and about and having the advantage of using firearms,” he said. Firearms have a longer range than bows.

Hunting bears in the heat

The early season, however, did raise concerns among some hunters. Some worried that the weather was too warm to hunt and that the meat would spoil before they could bring a bear in. Some also were concerned about low visibility because the leaves were still on the trees.

For Meservey, the heat was indeed a challenge. The temperature was in the high 40s when he shot his bear, and by noon it would reach 60 degrees. The bear weighed 580 pounds.

“I called everyone I knew to help,” he said. Five or six friends helped him roll the bear onto a wagon attached to a four-wheeler. They drove it to the nearby farm, where the owner let Meservey use a bucket loader to move the bear from the wagon to the back of his truck.

“I was low on gas and had to stop,” said Meservey. “Everyone was taking pictures of the bear. One couple from the city wanted their picture taken with it.”

He made it to the taxidermist in time, and when the rush was over, he donated the meat to the local church his parents attend.

“It was a production,” said Meservey, “but we all were able to enjoy it. The heat was the only downside.” Staten Island resident Steven Favorito said it was the warmer weather that lured him to participate in the early season.

“I wanted a bear all my life,” said the 27-year-old hunter, “and when the early bear season came about I knew this would be the year. Bears are most active that time of year than during the regular gun season.”

For three days, from sunup to sundown and through a rainstorm, Favorito waited in a tree blind for a bear -- until he finally saw and shot one around 4 p.m. on the third day in Olive.

With the help of his friend Nicholas Cross, he dragged the 160-pound bear a quarter of a mile out of the woods and headed straight for the taxidermist and the butcher.

“I’ve harvested a lot of bear,” said Cross, a Bearsville resident. “Steve hunted harder than anyone I’ve ever knew.”

Hikers v. hunters?

The early bear hunting season elicited concern from several outdoor groups, who argued it interfered with the safety and enjoyment of other recreational users of the Catskills, such as hikers.

Wendell George, chair of the activities committee of the Catskill Mountain Club, said that the club canceled one hike out of safety concerns. The club did hold another scheduled hike because it was in an area where hunting was unlikely, he said.

George said he wants to examine the final DEC data to determine if most of the bear hunting took place on private land or public lands in the Catskills Forest Preserve, where most hikes are held. If it appears much of the hunting is in the Preserve, George, who does not oppose hunting, said he was concerned that tourists and residents might perceive the Catskills are unsafe.

“How does it impact on the number of people who might otherwise have come to the Catskills for outdoor recreation? Those numbers are lacking,” he said.

The CMC has proposed other alternatives for managing the bear population, including increasing the bag limit per hunter, promoting bear hunting in neighboring states during the regular season, and prohibiting hunting in some popular hiking areas.

The Catskill 3500 Club, another hiking group, took a different approach. The Club, which encourages people to climb peaks over 3,500 feet in the Catskills, proceeded with hikes that had already been scheduled for the early season but reached out to participants to remind them to be careful and to wear blaze orange.

“Hike leaders who led hikes during the early bear season did report they had seen some small numbers of bear hunters, all encounters with the bear hunters were friendly, and this included both on-trail and off-trail hikes,” said 3500 Club Secretary Laurie Rankin.

At a 3500 Club board meeting in October, Rankin said that the Club decided to continue to schedule hikes for this September. It also changed a longstanding informal policy that prohibited the Club to lead trail hikes during the hunting season in November and December.

“We feel we can share the woods,” said Rankin, who added the policy change was based on recent feedback from hike leaders and its own review of historical hunting data.

“We are going to try it on trail peaks,” Rankin said. “That way, if you are a hunter or a hiker and you both sign in on the trail register, you are aware of one another’s presence.”

Bears on the rebound — and causing problems

The new early bear season is part of a 10-year black bear management plan approved by the state last year that aims, among other goals, to stabilize the bear population in some parts of New York and to reduce it in the Catskills and western Hudson Valley region.

Reforestation of abandoned farmland and hunting restrictions have led to a bear comeback since the 1970s, when the population was estimated to be around 250 bears in the Catskills range. Today, DEC biologists estimate there are between 1,800 to 2,800 bears in the area.

With the resurgence of bears has come an increase in the number of complaints about “nuisance” bruins who get into garbage or bird feeders or, more seriously, break into homes and cars.

In 2014, the five-year moving average for complaints about bears in the two DEC administrative regions that encompass the Catskills, increased 2 percent to 492 from 2013, according to DEC data.

Above: The number of complaints from the DEC Region 3 and 4 about bears filed with the state has increased every year since 2008, according to data from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

The number of complaints plays a large role in determining harvest targets and bear management strategy, said the DEC’s Merchant. Determining how many bears the Catskills can support depends not on natural habitat but on what biologists like Merchant call “the social carrying capacity.”

This capacity – or social tolerance – is the average attitude of humans who perceive negative and positive impacts of living in bear country.

Shawn Riley, a wildlife management expert at Michigan State University, said that when negative impacts (such as bear vehicle collisions, crop damage or people feeling threatened about personal safety) “outweigh positive impacts – the presence of bears in the ecosystem, the desire to see bears and view bears and the desire, perhaps, to hunt bears – then the social carrying capacity decreases.”

In other words, social tolerance of bears is dynamic, influenced by people’s circumstances and what they know about bears. A bear walking across a front lawn, for example, may be a joy to some but to a parent with young children perceived as a threat.

Sometimes the threat is real. In Sullivan County in 2002, a young bear snatched a 5-month-old baby from her stroller in a bungalow colony in the town of Fallsburg, killing her. That kind of deadly encounter with a bear is extremely rare.

The goal for wildlife managers is to reduce bear conflicts and to balance that with a healthy bear population.

“The sweet spot is managing the population at a level that produces the desired impacts perceived by society,” said Riley.

Finding the sweet spot can be a challenge in the Catskills, a region that is home to both a deep-rooted hunting culture and many residents who strongly oppose killing bears.

“Many people have a fear response to bears that is based on a lack of information about bears. We have come to a point in human evolution where we cannot ignore the interconnectedness of all things,” said Woodstock resident and outdoor educator Catherine Sklarsky.

“Education is the solution to bear intolerance. Killing individual bears is not going to solve any of the problems we are now facing," she said.

Apprehension over bears is on the rise. Merchant said that he’s noted a decline in the social tolerance of people coexisting with bears in the Catskills.

“There’s been some areas where people have gone from knowing how to tolerate bear behavior to a point where they are overwhelmed by bears,” he said. Bears seem to be damaging property more frequently, he said.

“Hunting is the main tool we use in wildlife management – it is the most efficient,” said Merchant. “One of our goals is to build up a bear hunting culture in New York.”

Correspondingly, the bear hunting season in the Southeast has been steadily lengthening. The number of days available to hunt bear increased from 78 days in 2013 to 93 days in 2014 in parts of the region where the early season was established. That followed another expansion in 2012, when the number of days increased to 79 days, up from 67 days in 2011.

Hunting as a management tool?

Using hunting as the main tool to reduce conflicts between humans and bears is, however, being questioned by a relatively new but growing body of scientific research.

In October, a peer-reviewed paper published by Ontario biologists reported they found no evidence that more hunting reduced human-bear conflicts in their Ontario study area, unless bear numbers are reduced to very low levels.

Those low levels, the paper noted, “might be at odds” with maintaining viable populations and providing opportunities for sport hunting.

A 2010 peer-reviewed paper published on a study in Wisconsin reached a similar conclusion.

Adrian Treves, the lead author of the Wisconsin paper, said that wildlife management agencies across the United States have based their main management tool – hunting – on an assumption.

Wildlife managers have also assumed that carnivores, like black bears, must be causing problems because they are too abundant, said Treves, who is a researcher at the Nelson Institute Carnivore Coexistent Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"It’s like an onion,” he said. “You peel away one layer, you find another [assumption]. In the past 10 years we’ve begun to test those assumptions. ”

In the Ontario paper published in October, researchers found that conflicts between humans and bears increased when natural food availability was low. The paper reported that educating the public and keeping bears away from human food work better at managing bear populations than increasing hunting does.

If experts disagree about the value of hunting as a management strategy for bears, then why do agencies across the United States do it anyway?

“That’s the $64,000 question,” Treves said.

Early season to stay, for now

Next year in the Catskills, the early bear season is scheduled to remain in place. It will be re-evaluated in five years to assess its impact on meeting the DEC’s goal to reduce the bear population, according to Merchant.

Hunters Meservey and Favorito said they will be ready. They both plan to head back out to the woods to hunt bears next September.

“One hundred percent,” said Favorito. “I wouldn’t miss it for the world.”