The place where 14-year-old Jordyn Engler drowned on the Esopus Creek on Saturday, Sept. 5 was near a notorious local river hazard. But that didn’t stop a Catskills tubing company from dropping her off at an abandoned tubing launch nearby.

The hazard, a heap of downed trees, piled up a decade ago near what was once a popular tubing launch location. It regularly destroys boats and gear, but it has never been removed. No signs warn of its presence.

Neither of the two tubing companies that work the Shandaken stretch of the Esopus Creek drop busloads of tubers at the site. But on Saturday, police say that the bus driver for F&S Adventures Tube Rental made an exception for Jeffrey Engler and his daughter, Jordyn Engler.

The two were on vacation from Ellington, Connecticut, where Jordyn was a freshman at Ellington High School and a cheerleader on a nearby all-star team. They were visiting a spot where Jeffrey Engler had tubed many times before, and planned to float downriver to the hamlet of Phoenicia.

But minutes after getting into the water, Jordyn drowned in her father’s arms, pinned against a log by the pounding current.

Above: Jordyn Engler in an Instagram photo.

Unscheduled stop

The Engler family has asked for privacy in the wake of the tragedy, so we did not contact Jeffrey Engler for this story. This account comes from the Ulster County Sheriff's Office, which interviewed F&S and Jeffrey Engler after the incident, as well as first responders and other sources familiar with the circumstances around Jordyn Engler's death.

That morning, Saturday, Sept. 5, Jordyn and Jeffrey Engler rented their inner tubes and climbed onto the bright green F&S bus that ferries tubers to upriver launch points, police say.

Onboard, Jeffrey Engler asked the bus driver to make an unscheduled stop at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation fishing access point on Route 28 next to the Shandaken Rural Cemetery in the hamlet of Allaben.

[According to Jeffrey Engler, this account is false. F&S agreed to make a special, private trip to drop the Englers off at the site, Engler said, and the bus was otherwise empty. See Engler's full account in our follow-up story by clicking here. - Editor's note, Oct. 1, 2015.]

Above: The sign for the DEC fishing access point at the Shandaken cemetery. The site was once a popular tubing launch spot. Photo by Julia Reischel.

The site isn’t one of F&S’s launch sites—the bus driver was planning to take his passengers farther upstream.

[Several witnesses, including Jeffrey Engler, dispute this. They say that the bus was empty except for the Englers. See our full follow-up story here. - Editor's note, Oct. 1, 2015.]

That’s because just a few dozen yards downstream of the Shandaken location is a “strainer,” a pile of downed trees and debris that hugs the eastern bank of the stream. In 2005, a flood deposited it there, creating a hazard where the water narrows and deepens, boiling through the sieve of downed trees and rocks.

Because of the strainer, both tubing companies that operate on the Esopus Creek stopped dropping tubers off at the spot.

“We haven’t used that launch site since 2005 because of the dangerous strainer,” said Harry Jameson, the owner of Town Tinker Tube Rental, which is also based in Phoenicia and competes with F&S.

But before 2005, the Shandaken cemetery was a popular tubing launch location. Jeffrey Engler remembered it fondly.

“[He] had been tubing there, he said, 30 times at least,” said Capt. Kevin Altieri of the Ulster County Sheriff’s Office, who investigated Jordyn’s death.

Engler asked the F&S bus driver to make a special stop for them, police say.

At first, the driver refused, police say. But Engler was reportedly persistent.

Above: F&S Adventures Tube Rental in Phoenicia. Photo by Julia Reischel.

So the driver agreed to allow the Englers to get off at the cemetery. They could check out the conditions themselves, he said, and if they didn’t look good, the driver would turn around after dropping the other tubers off at the designated launch site upstream and would pick up the Englers on the way back.

When the bus driver returned as promised, Jeffrey Engler waved him on, police say, indicating that he and his daughter would launch from the unauthorized site.

The bus driver drove on, police say.

[Jeffrey Engler and other witnesses say that they did not see the bus return, and that Jeffrey Engler never came back up the path to wave the bus on. - Editor's note, Oct. 1, 2015.]

The owners of F&S declined to comment for this story. The business has been closed in the days following Jordyn Engler’s death.

According to Jameson, who runs tubing trips along the same stretch of river, Engler’s request to launch from the off-limits Shandaken cemetery site is not unusual.

“There isn’t a time a bus goes by there that we don’t get asked, ‘Can we stop here? Is this as far as we can go? Can’t we go farther upriver?’” Jameson said. “My job is to tell them, ‘No, it’s too dangerous.’”

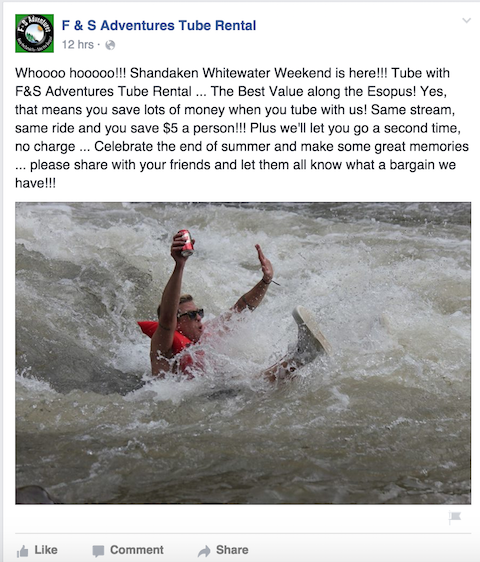

Shandaken Whitewater Weekend

From the small parking lot next to the cemetery, a dirt trail winds through scrub and emerges on a rocky streambank next to the wide, shallow Esopus, which splits into two around a large gravel bank.

Above: The trail to the Esopus Creek at the Shandaken cemetery. Photo by Julia Reischel.

It was around 11 a.m. when the Englers arrived at the water’s edge. Although it hadn’t rained for weeks, the Esopus was raging.

The New York City Department of Environmental Protection, which controls the water levels in the river, had opened the gates of the Shandaken portal to flood the stream with water piped along an 18-mile tunnel from the Schoharie Reservoir.

The extra water was for recreation. Tubing companies and outdoor enthusiasts request that the DEP release extra flow a few times a year to create whitewater conditions for kayaks, canoes and tubers. The Labor Day release was promoted by the tubing companies as “Shandaken Whitewater Weekend.”

Above: A Facebook post advertising "Shandaken Whitewater Weekend" on the F&S Adventures Tube Rental Facebook page.

Thanks to the bonus water, the Esopus was running at about 800 cubic feet per second, more than double its usual flow.

Even in the furious stream, the strainer downstream of the cemetery fishing access point didn’t look that dangerous. A few large dead trees jut into water, which is about five feet deep. Debris is wedged around them. People floating by on inner tubes from launch sites further upstream can pass right by on the other side of a central gravel bar and not even notice the hazard.

[No tube rental company currently drops tubers at launch sites upstream, according to Harry Jameson, who spoke to us for a follow-up story. - Editor's note, Oct. 1, 2015.]

Above: The strainer where Jordyn Engler drowned, as seen from the river's edge at the Shandaken cemetery fishing access point. The strainer, which is the pile of debris on the lefthand side of the photo, is easy to overlook. Photo by Julia Reischel.

“If you see debris while you’re going only a few miles an hour, you just don’t think that it’s dangerous,” said Altieri, the captain with the Ulster County Sheriff’s Office. “You think that you’re going to float down through on the lazy river.”

But locals know that the strainer is extremely dangerous. Last summer, Marc Hollander, the co-chair of the Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program’s Stream Access and Recreation Committee, had a friend hold him with a rope while he dangled out over the strainer in an attempt to retrieve lost whitewater gear.

Last December, Hollander featured the strainer In a PowerPoint presentation to the committee, calling it out as an exceptionally hazardous spot on the Esopus for boaters and tubers.

Above: A slide from Hollander's PowerPoint presentation with a view of the strainer at the Shandaken cemetery.

After Jordyn's death, Hollander called the strainer “an obstruction that's deadly to anyone in the main current of the river."

“I feared that Saturday's tragedy was sure to come,” he said.

Still, when Hollander visited the site the day after Jordyn’s death, he saw several people wading within 100 feet of the hazard, oblivious.

“I told them they were in a bad place,” he said.

Above: Peter Oberbeck, a trout fisherman, standing near the strainer where Jordyn Engler drowned the day after her death. Photo by Julia Reischel.

Before the Englers arrived the riverbank on Saturday, Peter Oberbeck, a trout fisherman who fishes the river at that location almost daily, warned a kayaker about the strainer.

“I told her, ‘Don’t go here,’” said Oberbeck, who was fishing there again on Sunday. “I have seen kayaks in it; I’ve seen a canoe in there that was crushed.”

But by the time the Englers arrived, Oberbeck had left. The stretch of river was empty. No one warned them.

Immense pressure

Minutes after arriving at the Esopus Creek at the cemetery fishing access point, the Englers were sucked into the strainer, police say.

[Jeffrey and Jordyn Engler were wading in the stream carrying their inner tubes when Jordyn slipped on rocks, Jeffrey Engler said. Read our follow-up story by clicking here. - Editor's note, Oct. 1, 2015.]

With a current so strong that a grown man couldn’t stand upright in it, the water pinned them against a large log which was connected to the shore.

Both Jeffrey and Jordyn were wearing life preservers, and Jeffrey managed to grab onto Jordyn. But Jordyn, who police estimate weighted about 90 pounds, was not able to fight through the current to climb out of the water onto the log. With the pounding stream pouring over them both, Jeffrey couldn’t lift her clear, either.

“Apparently, with the force of the water, he just couldn’t lift her up onto the log,” Altieri said.

Above: The log where the Englers were trapped on Saturday, Sept 5. Photo by Julia Reischel.

Minutes passed. The immense pressure took its toll on Jordyn’s life jacket, which was not designed to withstand such forces. Part of it snapped. It slipped off and disappeared.

[Jeffrey Engler said that this is incorrect. He removed Jordyn Engler's life jacket in an attempt to save her, he said. - Editor's note, Oct. 1, 2015.]

Now Jeffrey Engler was the only thing keeping his daughter above water.

“And then he was holding her,” Altieri said. “He was holding her until he couldn’t keep her head above water. He was still holding her when she went limp.”

By 11:15 a.m., Jordyn Engler had become unconscious in her father’s arms, police say.

“This poor man actually watched his daughter drown,” Altieri said.

“It’s just too dangerous”

Deaths on the Esopus are rare, but not unheard of. In 2002, a 17-year-old tuber and a kayaker drowned in the river, both caught in strainers, according to the Times Herald-Record and the New York Post. In 2009, a man died while tubing on the river near the Sleepy Hollow Campground in Phoenicia, his legs caught by “an underwater obstruction,” according to the Times Herald-Record.

But the death of Jordyn Engler is different. First responders who spent hours at the scene treating Jordyn’s father and trying to recover Jordyn’s body say that this call is one of the worst they’ve ever had.

“I’ve been to a lot of calls; I’ve been on the job for 30 years,” said Altieri. “Having that man know—what he had to have seen—is the most horrible thing.”

After Jordyn’s body slipped from his grasp, Jeffrey Engler was also carried away by the current. He was swept to the opposite bank of the river, banged up but largely uninjured, first responders say. Then he screamed for help, eventually attracting the attention of a kayaker, according to the the Hudson Valley News Network.

By the time first responders arrived, Jordyn had been underwater for 20 to 30 minutes. They knew it was probably hopeless.

Above: Rescuers search for Jordyn Engler in the high water of the Esopus Creek, which is running at about 800 cubic feet per second in this video. The video was shot by a first responder at the scene and shared with the Watershed Post.

Still, almost 60 first responders from a number of Catskills ambulance companies, fire departments and agencies spent hours looking for Jordyn. Several of them risked their own lives in the process.

Above: A sunken swiftwater rescue boat sits next to the log where Jordyn Engler's body was recovered. The river in this photo is much lower than it was when Jordyn drowned. Photo by Julia Reischel.

Trying to reach the spot in the strainer where Jordyn was trapped underwater, rescuers lost two swiftwater rescue boats and narrowly escaped losing two men, Altieri said.

Boarding a small inflatable boat anchored by a rope held by rescuers onshore, two swiftwater responders shot down the river toward the strainer. The boat hit the log that had trapped Jordyn and flipped, ejecting the two men, Altieri said.

“When they hit that log, the water was raging over the top of the log,” he said. “The guys in the boat were hanging on one side, and the boat just flipped. The two guys fell out, and they landed on the log.”

Had they landed in the water, they could have been sucked under just as Jordyn had been, Altieri said. They were incredibly lucky.

“If they had gone over the log when the boat flipped; if they had gone over the log into that debris, it’s possible that they couldn’t have climbed up,” Altieri said.

Concerned that another try might not be so lucky, the first responders sent another boat, unmanned this time, towards the strainer as a test. To be safe, they anchored it with an extra set of ropes held by eight men onshore.

This time, the river folded up the boat and sucked it under the log.

“It pulled probably eight guys almost off their feet, that’s the amount of power it had,” Altieri said. “You absolutely couldn’t budge it. Within ten minutes, the boat was crushed. It’s lined with metal—aluminum. It was just intense power.”

Above: One swiftwater rescue boat was completely crushed by the stream. Photo by Julia Reischel.

After that, the rescuers decided that it was too hazardous to work in the whitewater conditions on the strainer. They called the New York City DEP and asked the agency to turn off the Shandaken portal, shutting down the extra flow into the river.

“We said, look, it’s just too dangerous,” Altieri said.

That meant there was no longer any hope of finding Jordyn alive.

A boat full of bullet holes

It takes hours for the closure of the portal to affect the flow of the Esopus Creek. The tunnel from the Schoharie Reservoir is 18 miles long. It was 6 p.m. by the time the river level had dropped enough for rescuers to safely get into the creek to recover Jordyn’s body.

Above: Rescuers search for Jordyn Engler's body after requesting that the Shandaken portal be closed, restricting flow to the Esopus Creek. The flow of water in this video is much lower than it was when Jordyn Engler drowned and rescue operations began. The video was shot by a first responder at the scene and shared with the Watershed Post.

With the water level lower, rescuers were able to stand in a third swiftwater rescue boat with a chainsaw, which they used to saw through pieces of the log that had trapped Jordyn.

Above: A sunken swiftwater rescue boat full of bullet holes next to the log which rescuers cut using a chainsaw to free Jordyn Engler's body. The river in this photo is much lower than it was during initial rescue attempts. Photo by Julia Reischel.

“Eventually, they were able to get her free,” Altieri said.

Even then, the river near the strainer was dangerously strong.

“Even with the water going much slower, it was too strong for the guys to stand,” Altieri said.

As they left the scene, the first responders performed a final act: they destroyed the damaged rescue boats so that they wouldn’t become a new hazard themselves.

One, near the shore, they poked full of holes. They couldn’t reach the other boat, farther out in the stream, so they shot it full of bullets.

“We were afraid that someone would think, ‘Oh, I can go get that, and retrieve it and salvage it,’” Altieri said. “Then we would be there trying to save somebody else.”

“The liability question”

The issue of removing strainers and other hazards from recreational Catskills waterways is a contentious one with a long history.

“I’ve been involved in the issue for 30 years,” said Harry Jameson. “The 1987 flood; that’s when I made my first phone call to the DEC, and asked them why, on the one hand, you have the New York State department of economic development promoting the Esopus as a recreational waterway, and on the other you have the New York State Department of Conservation basically turning a blind eye to public safety.”

According to DEC policy, strainers like the one where Jordyn Engler died should not usually be removed unless they threaten bridges or other infrastructure, according to a DEC fact sheet on debris removal, which notes that woody debris is a vital part of healthy stream ecosystems.

When debris causes safety concerns, a tangled web of conflicting property rights and a fear of liability make it hard to simply remove it from the stream.

“The bigger question is not the physical removal, or the cost to do it,” said Harry Jameson. “It’s the liability question.”

Jameson could request a permit from the DEC to clean up the strainer himself, he said. But then he could be liable for anyone who might be injured on or near the site.

Leaving debris in the water doesn’t prevent lawsuits, either. After the tubing and kayaking deaths involving strainers on the Esopus in 2002, lawsuits were filed against landowners.

A 2007 Upper Esopus Creek Management Plan sums up the problem.

“Exploring solutions for large woody debris management that provide multiple benefits is recommended, but has proven difficult,” the plan stated. “The pivotal question remains: “Who is responsible for large woody debris when it falls into the Esopus Creek?”

In an email to stream recreation advocates on Monday, Marc Hollander cited “too much fear of litigation” as the number one issue threatening the safety of recreation on the Esopus.

“Let's get over this where safety is a concern,” he wrote. “Time to evolve.”

Correction: Jordyn Engler was not a cheerleader at Ellington High School, but rather a member of an all-star cheerleading team called Fierce based in Manchester.

Editor's note: Jeffrey Engler asked for privacy after his daughter’s death, so we did not interview him for this story. After publication, Engler contacted us to describe his experience of the day in an attempt to correct what he called errors in police and media accounts of Jordyn Engler's death. We have marked the discrepancies between Engler's account and the initial police account throughout this story. The Ulster County Sheriff's Office, which has closed its investigation and has determined that Jordyn Engler's death was an accident, does not dispute Jeffrey Engler's account of the incident. Click here to read our follow-up story about our interview with Jeffrey Engler.