We're trying something new today at the Watershed Post: a theater review. Kirby Olson, our resident poet laureate, submitted this review of Trojan Women at the Franklin Stage Company. (We wrote about the show, which is playing for two more weeks, last week.) If you'd like to submit a review of a performance, a concert, or an art show, please send it to us at editor@watershedpost.com. -- Julia Reischel

My daughter Lola got an offer to play Polyxena at Franklin Stage Company this summer.

I knew Polyxena was part of the Trojan War cycle, but couldn't remember the details. We did have the Brad Pitt version of Troy a few years back. I have read the Iliad and the Odyssey, but I couldn't remember Polyxena. It seems that a later writer, Euripides, added Polyxena, because she's not in Homer. Polyxena is the younger sister of Cassandra, the daughter of the Trojan king Priam. If you recall, Cassandra is a prophetess who can foresee the future accurately but is cursed with the fact that no one will believe her. She foresees the fall of Troy from the moment that her brother Paris brings home Helen. Everything Cassandra foresees comes true. Polyxena is about fourteen (whereas my daughter is twelve).

The play opens with Troy a smoking ruin under military domination by the Greeks. The illegitimate son of Achilles appears on stage looking like an American GI in Iraq. It’s strangely realistic. I was holding my 7-year old son in my lap and he said, “Dad, I’m scared.” They started talking about whether or not Polyxena will be killed. “Hey, she’s my sister!” my son whispered in my ear.

There was blood all over the GI’s arms. It wasn’t his blood. He had just chopped off the king of Troy’s head. Meanwhile, the remaining Trojan women are talking about what will become of them. They are being divvied up by the top Greek generals as slaves. One will get Hector’s wife, Andromache, another will get Helen of Troy, another will get Hecuba, Priam’s wife, and still another will get Cassandra and yet another, Polyxena. "What’s left to mourn?" the women wail.

Hector, who had been the Trojan’s champion, is dead. His baby boy has to be ferreted out and killed by Ulysses -- played with verve as a British comedian by Peter Gaitens -- or else the winds won’t take the Greek ships back across the Aegean Sea. Polyxena has to be killed too. She was betrothed to Achilles, but told her brother Paris about his weak spot, the heel. Paris uses this information to shoot Achilles in the heel with a poisoned arrow. So Achilles is calling from beyond the grave for Polyxena’s death!

I’d read the script by Seneca in several translations and this one is the easiest to follow. The translator, David Slavitt, was present at opening night. He said the trick with Seneca is to be clear but to have a touch of poetry. I told him I was Polyxena's dad and he said, "I was pleased with her work. Give her a hug for me, will you?" (I did.)

I spoke with other actors and the director after the first show. Agamemnon, who is played by Charlie Kevin, is a study in ambiguity. Charlie Kevin said Agamemnon is a warrior, but he is beginning to see the light. Violence begets violence. Seneca lived under the Emperor Nero. Seneca’s entire family was killed by Nero (on the basis of a suspected assassination plot), and he, too, was forced to commit suicide. Perhaps Seneca had foreseen his own family’s fate in that of the Trojan women? Kevin’s Agamemnon towers over the stage. But he realizes if Troy can fall, so can he. So can anyone.

Paris’ poor choice of Helen (played for laughs as a Lindsay Lohan type by Kathryn Saffell) threatens to throw all the marriages of Troy into disorder as men are forced away from their families into a decade of war from which most never return. Cassandra (played by Elizabeth Hope Williams) rivets the audience as she writhes with prophesies.

One of the finest moments in the play is the final soliloquy in which Hecuba (mother of Polyxena and Cassandra) asks whether or not we are surrounded by “nothing but black space,” and might as well worship the "night and cold." Hecuba (played with regal indignation by Carmella Marner) dares the gods to reveal themselves.

The harrowing ending reveals Rome’s poverty in the midst of its wealth. Seneca's play, written roughly at the same time as Christ’s death on the cross, reveals Rome's readiness for a metaphysical counterattack. Rome has been gone for well over a thousand years, while the Jews and their prophet are still very much alive.

The play is a lovely hour and a quarter: the pacing is fast, the staging inspired. But the world beyond the play is something I want to mention. My daughter Lola found a family amidst the equity actors, as well as the director and her husband and their year-old baby, Emeris. They were not only welcoming, but made sure she was nourished by their warmth and friendship. It was a special summer for Lola. She got to die every night, but it was her first taste of life!

The Trojan Women, by Seneca. Franklin Stage Company, Chapel Hall, 25 Institute St., Franklin, NY. Wednesday, August 17 to Sunday, September 4. Wednesday to Saturday, 8 pm, with a matinee on Saturdays at 2 pm, and the show on Sunday at 5 pm. Free, but donations are welcomed. Call 607-829-3700, or email reserve@franklinstagecompany.org for reservations. The play is not recommended for children under 12. www.franklinstagecompany.org. For more info, see the event's listing in our Catskills community calendar.

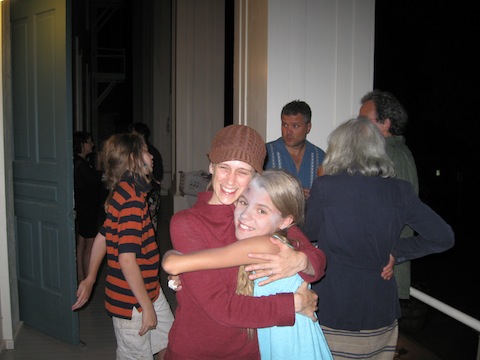

Illustration by Gary Mayer. Below, director Mollye Maxner hugs Lola Olson after opening night. Photo by Kirby Olson.